Robots and Comics

A peek inside the robot lab of a comic book artist’s son

A couple of months ago, the original Segway was discontinued. It reminded me that several years ago Segway inventor Dean Kamen was kind enough to participate in my series of inventor portraits and there are some interesting parts of that story that have never been told. At the time, the Segway had already been out for a while and the latest thing he was developing was a DARPA-funded robotic prosthetic arm named Luke (after Luke Skywalker). This is the story of my visit to the lab, with many never-before-seen images.

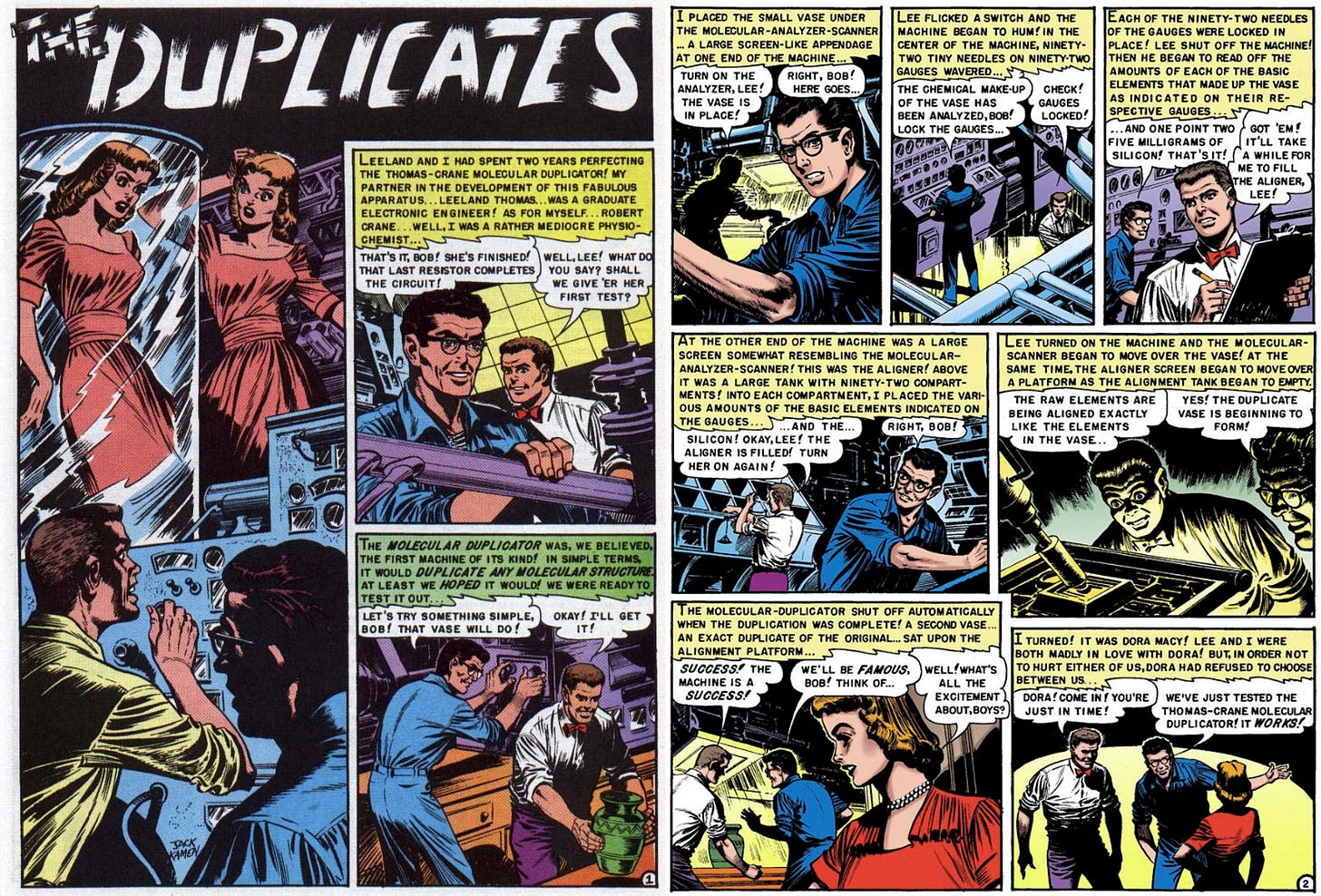

Before we continue, one thing to know for this story is that Dean Kamen’s father Jack Kamen was a comic book artist. He worked for EC Comics, publisher of Mad Magazine and Tales From The Crypt, among others. Here are a couple pages from a story he illustrated called “The Duplicates” from Weird Fantasy #9 from September, 1951:

Keen eyes will notice that the left page is a scan from the original comic, and the right page is from a recolored version that was released much more recently. I prefer the original coloring.

I was going to have around 45 minutes with Dean. In that time, I hoped to fit in several different photo setups and shoot a video interview. I had one idea for a specific photo: I wanted to take a photo of him posed like Rodin’s Thinker, with his chin resting on his fist, but we’d use the robotic hand in place of his own. My point of contact at DEKA (that’s the name of his company — as in DEan KAmen) said the robotic arm would be available for the shoot.

For the interview, since I’m as much a fan of art as science, I had a couple questions about his father planned. But I didn’t know if it was a subject he liked to talk about. It turned out it would be easy to broach the subject, as his father’s artwork was all over the place.

When I arrived at DEKA, my first glimpse of Jack Kamen’s art was in the lobby. Before the Segway, Dean Kamen had used self-balancing technology in a wheelchair that could stand up on two wheels, go up stairs, and roll easily across sand. It was called the iBOT. And there was a painting in the lobby featuring several people using the iBOT. It was a little cheesy but kind of beautiful, like art from a 1960s magazine ad for the iBOT.

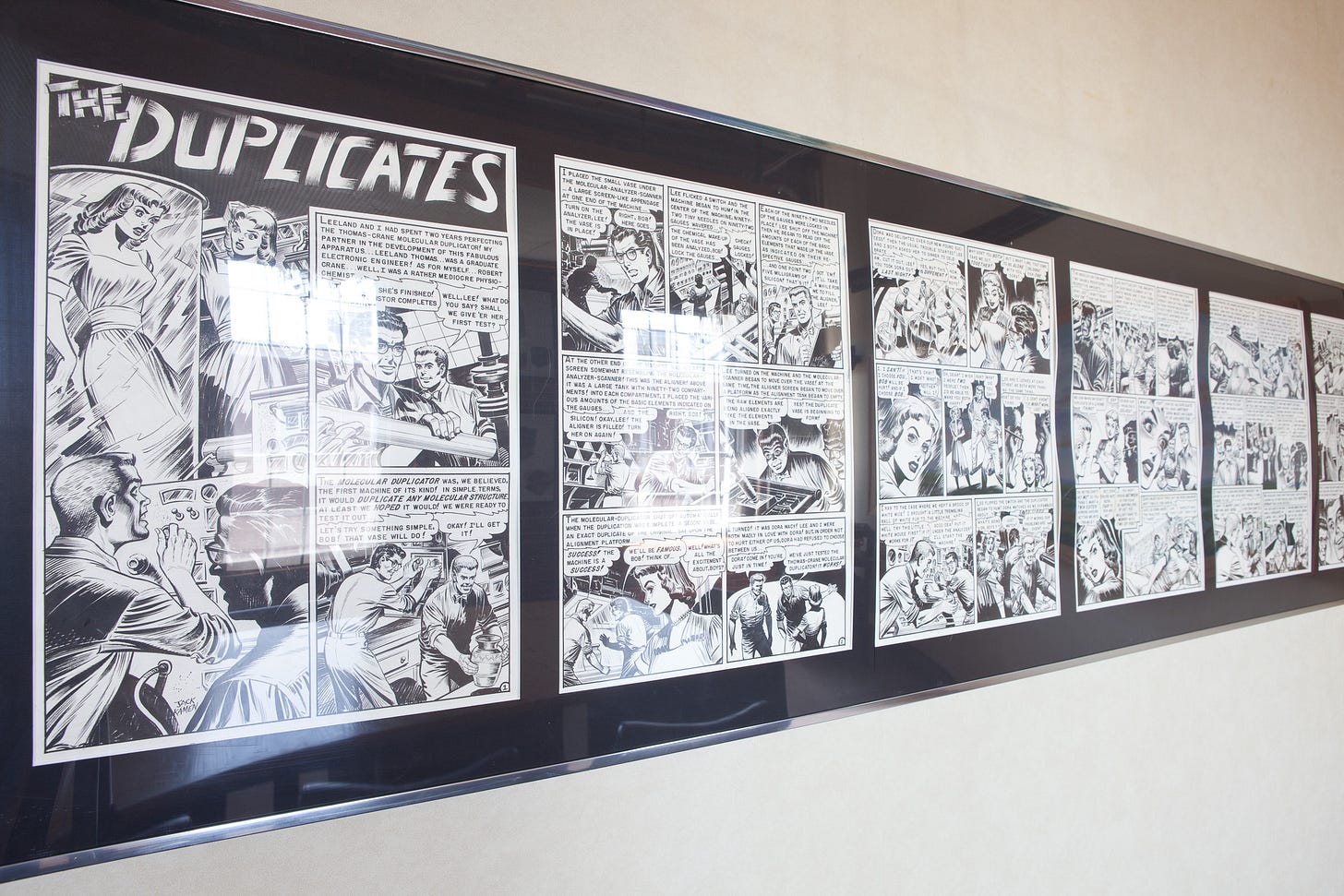

I was escorted from the lobby down a hallway to a conference room near Dean’s office where I could set up. In the hallway I saw more of his father’s art hanging on the wall. There were the original inked pages from “The Duplicates” from Weird Fantasy #9 from September, 1951:

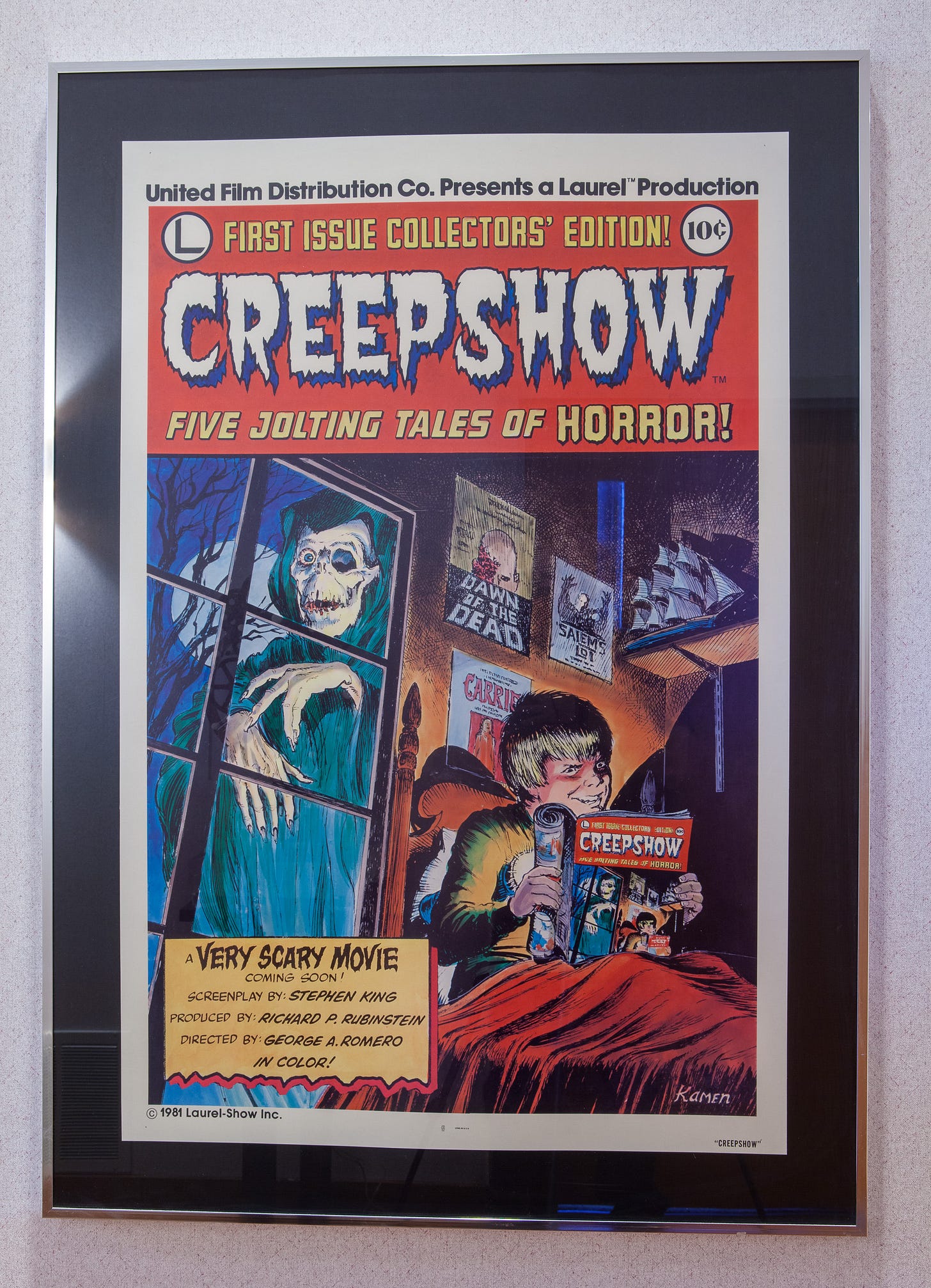

And nearby in the same hallway was a poster for the movie Creepshow, Stephen King’s homage to the old EC horror comics, illustrated by Jack Kamen. (This poster also makes use of the Droste effect which is a fun thing you can tell your friends about).

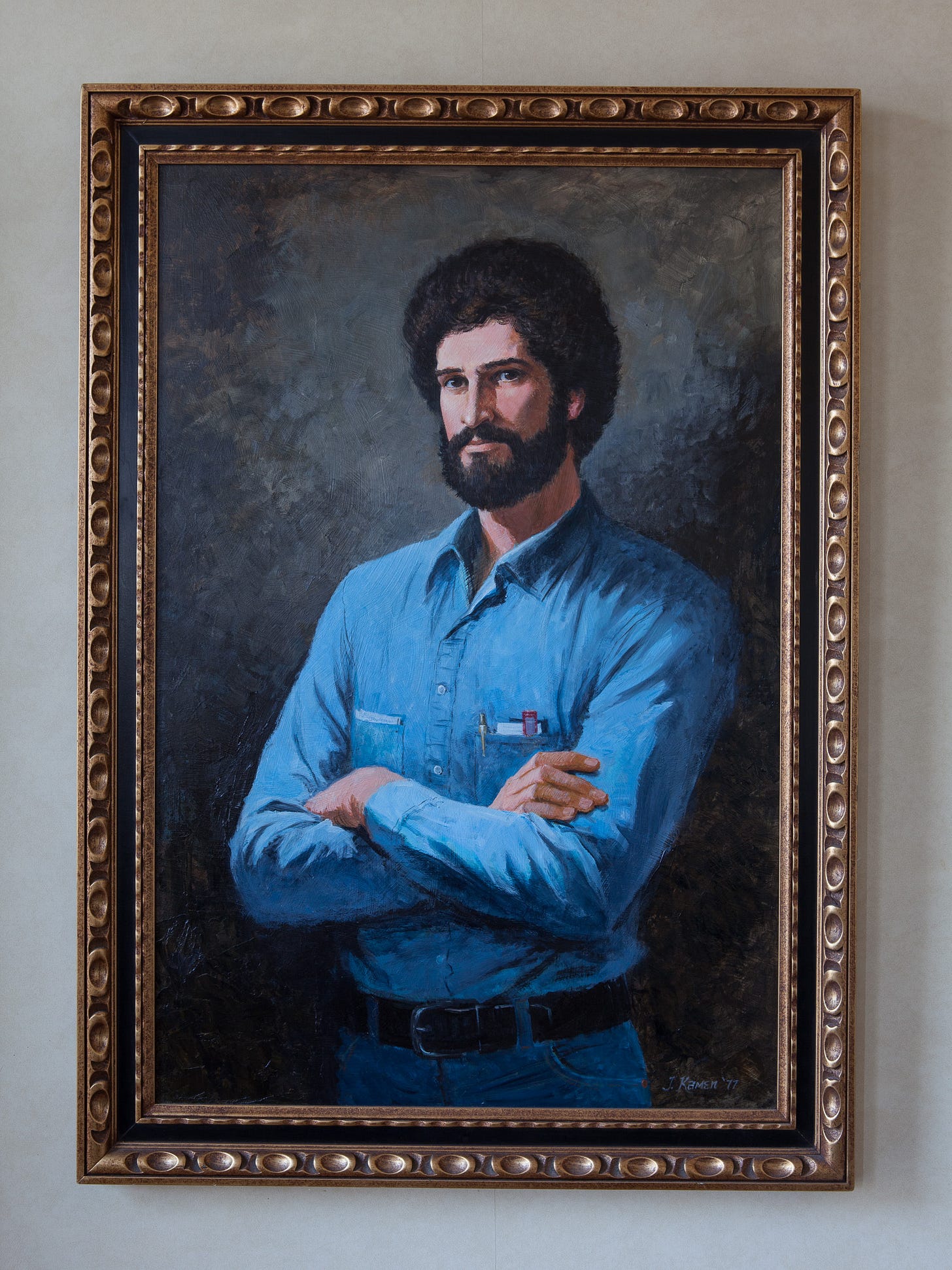

I got to the conference room that would be my staging area. My assistants and I loaded in our equipment, and I looked around the room. That’s where I saw maybe my favorite Jack Kamen painting in the whole place. It was a 1977 painting of Dean Kamen sporting an awesome beard and hairdo, already wearing his signature denim-and-denim uniform. (I guess I’m just assuming the shirt is meant to be denim because I hope it is.)

As we unpacked the gear I asked my escort about the prosthetic arm, and that’s when she hit me with the news: the arm wasn’t available! One of the engineers was using it for something that day.

I was disappointed. That was the one concrete idea I had coming in. I was sure I would still find some good photos to take, but I had looked forward to working with the arm.

Before long, Dean showed up.

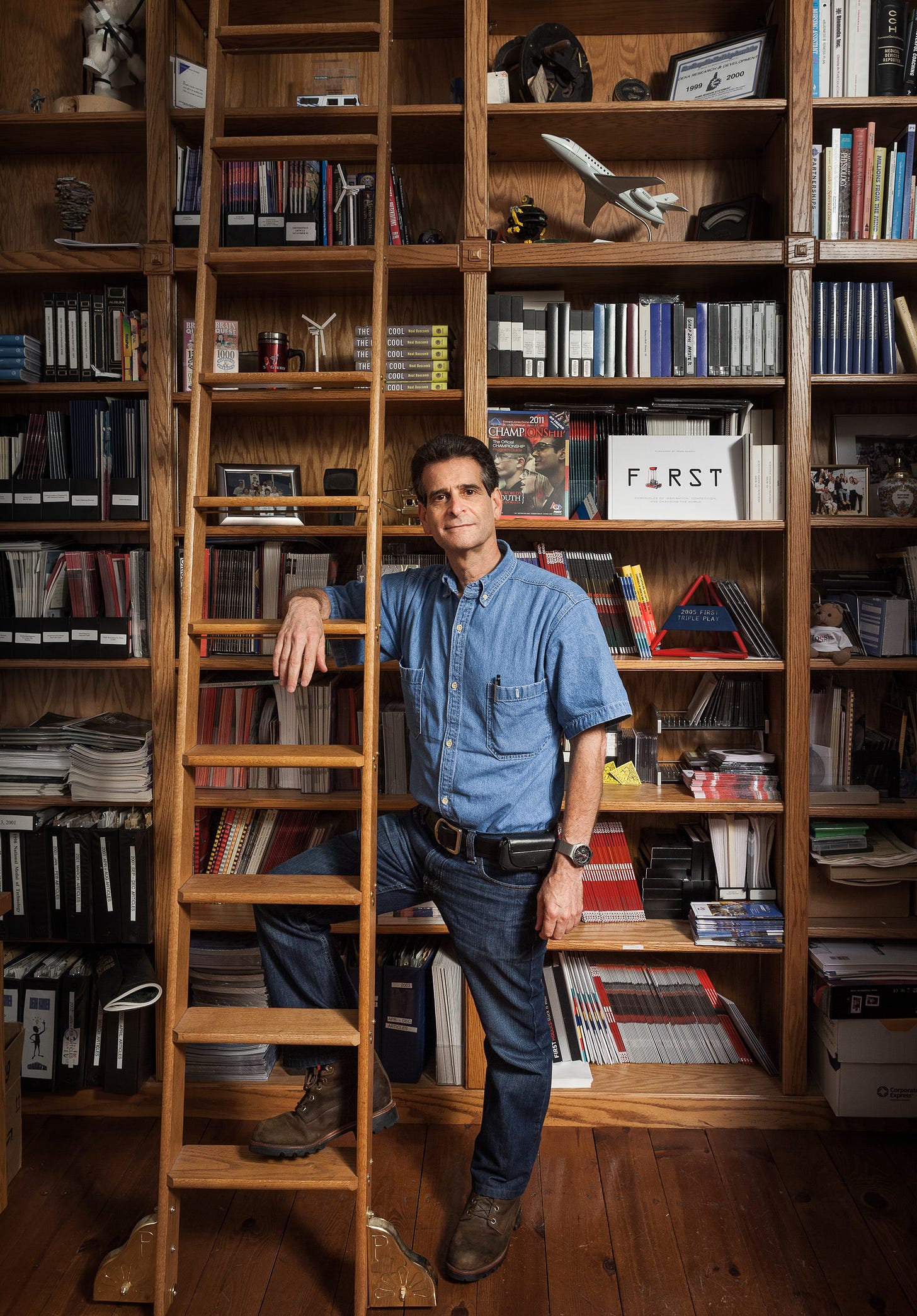

We took some shots in an area just outside his office that I thought looked nice:

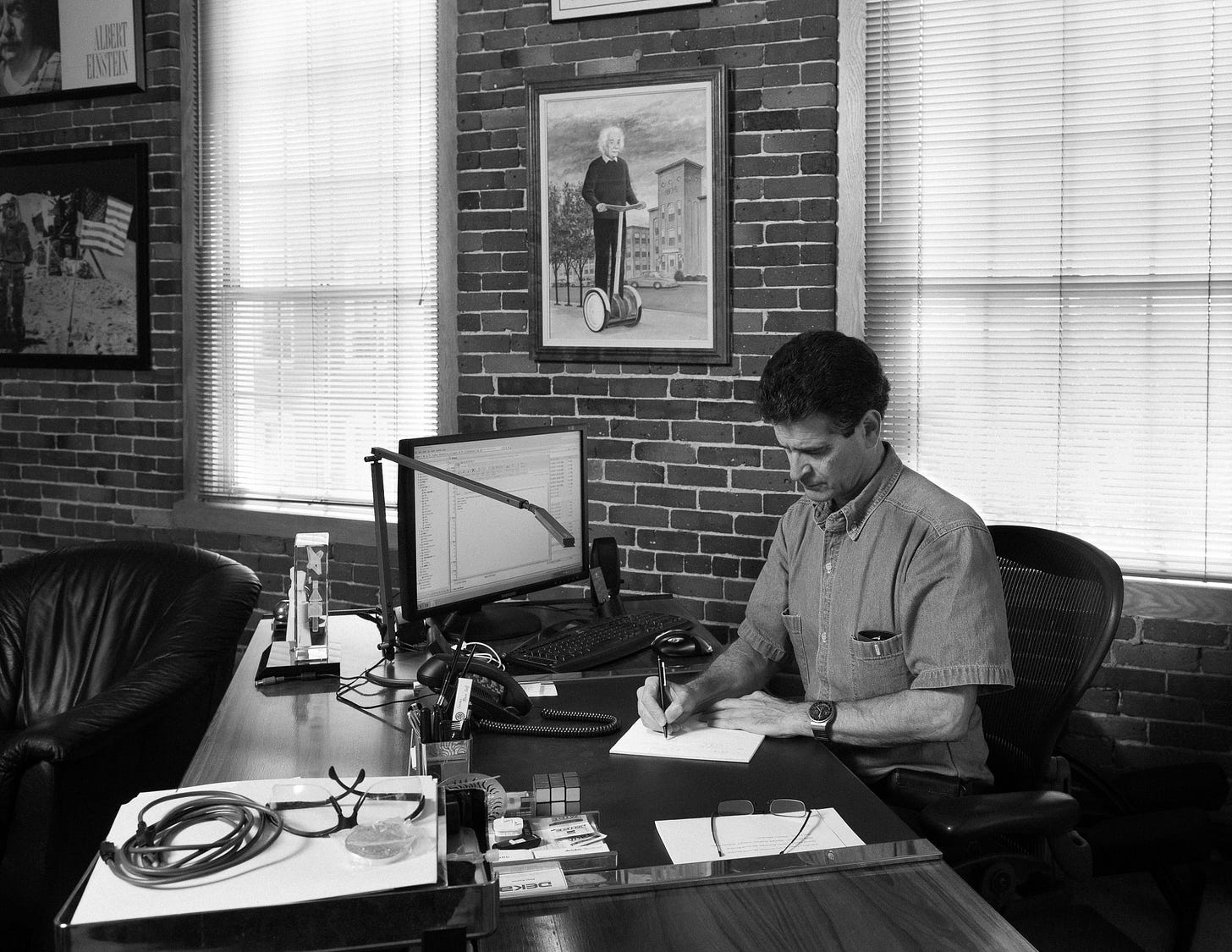

And we shot some pictures in his office while he pretended to work:

Wait, what’s that in the background? Is that a painting of Albert Einstein riding a Segway in front of the DEKA building?

It is! And it’s another Jack Kamen painting!

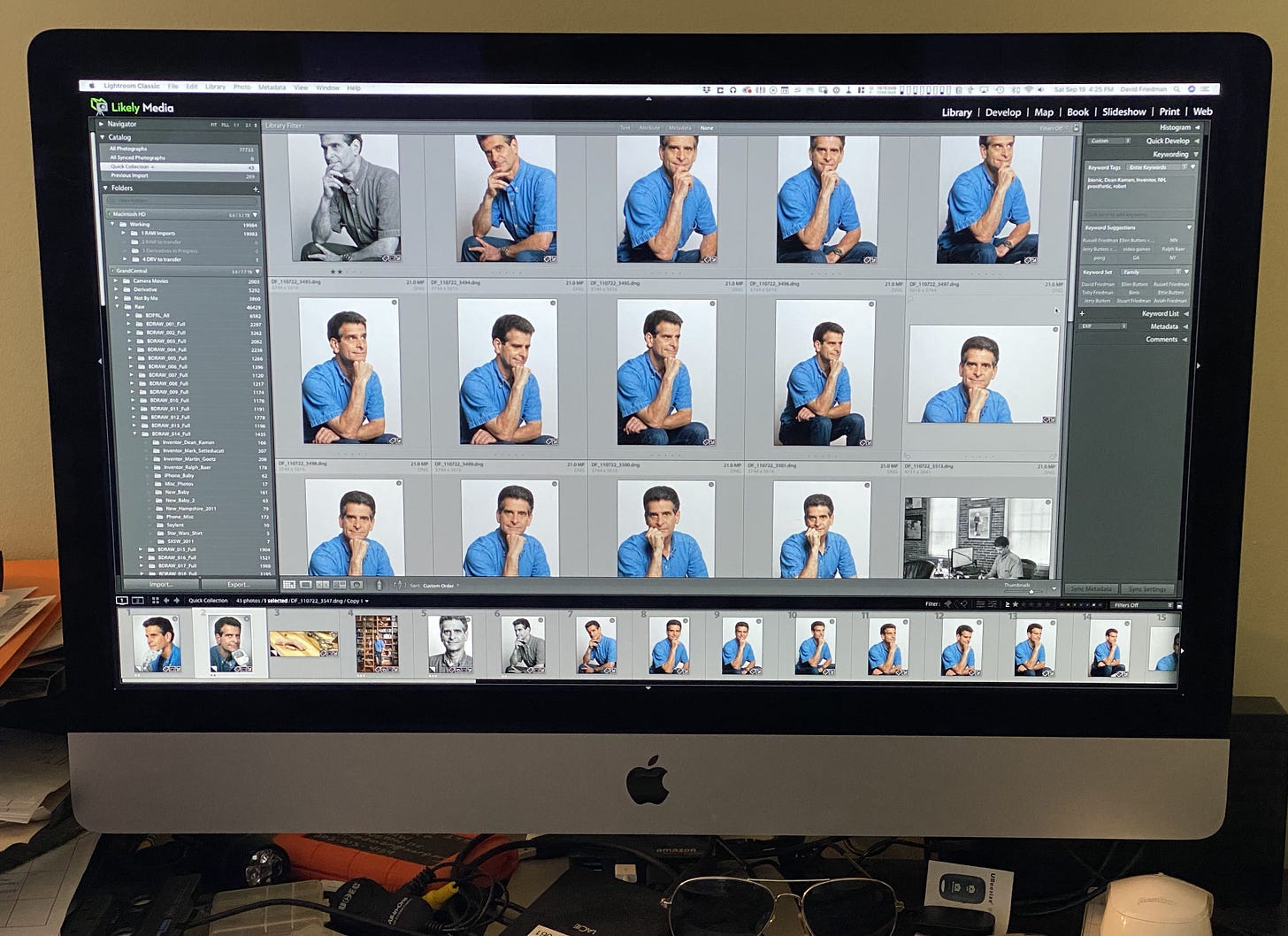

Then we moved to the conference room where I had set up a white backdrop. One of the conditions for Dean participating in my project was that I had to take a headshot they could use for free. That seemed like a fair trade. So we took some headshots:

And while we were there with the white backdrop, I figured I might as well try to take some pictures of him sitting like The Thinker. But my heart wasn’t into it without the robot arm. And, friends, the photos were not especially great.

I dunno, maybe that one on the top left was okay.

I shot a few frames and we finished the shoot and moved on to the interview. And as part of it I did ask him about his father, and the role of art in science (and if you’ve read this far, stick around — the robots are still coming):

Q: I know you're a big proponent of STEM [Science / Technology / Engineering / Math education]. A lot of people say it should be STEAM -- you should add the A for Art. Given your father's career, is there anything you have to say about that?

A: I'll give you a disclaimer that my father was an extraordinary artist. He was born with a talent and a gift that you can't train into somebody. Artists are born. Physicists are trained. I can't draw a straight line with an edge. I have no artistic talent. At one point I pointed that out to my father who I think was being very kind and he said, “Actually, Dean, I think you and I are very similar. We both create things. We just use different tools.”

And after he said that I thought about it quite a bit and decided that actually my father and I are very similar. I used to think we couldn't be more different. He's an artist. My world is around science and math and physics. But after he said that it occurred to me he gets up every morning and creates something new and hopes the world wants it and likes it and accepts it. And every day I show up at DEKA and working with my engineers we try to create new and different solutions to what we think are big problems: global issues of water, or people that need to treat their diabetes, or that need dialysis, or that need stents, or that need help with mobility, but we try to find new and different ways to combine the newest technologies to meet a real human need. And I guess similar to my father, we're trying to be creative and we're trying to offer the world alternatives that didn't exist before we started puttering around.

Q: So then in terms of art going along with science, do you think that it should be emphasized as a complete package, that art education should go along with it? Or do you think they're separate realms?

A: I think trying to debate which is more important — art or science — is kind of a naïve simplistic discussion that maybe little kids should have. It's a meaningless and irrelevant conversation. Science and technology are critical to establishing our standard of living, our quality of life, our healthcare and security. But without art, without context, without a reason to express ourselves and understand each other, what's the point? You know? I hear very frequently people try to make it an either-or, but a broad-based intellect I don't think can exist without both of them.

Fantastic answer.

We wrapped up the interview. I thanked him for his time. And then I figured, as long as he’s here, why not just ask one last time about the arm? What could it hurt?

“Dean, before we finish, is the Luke arm available for a couple photos with you? I heard it was being used for something else today.”

“Oh, sure. We can get it.” Yes! “Follow me.”

Follow him? Okay! Where?

He led me down a hall, through some doors that he had to swipe a badge to enter, down a stairwell, through some more badge-swipe doors and hallways — in fact I’m putting this clause here in order to artificially make this a longer sentence to help convey just how long it seemed to take to get where we’re going — and finally we entered a large room that looked like something out of a science fiction film.

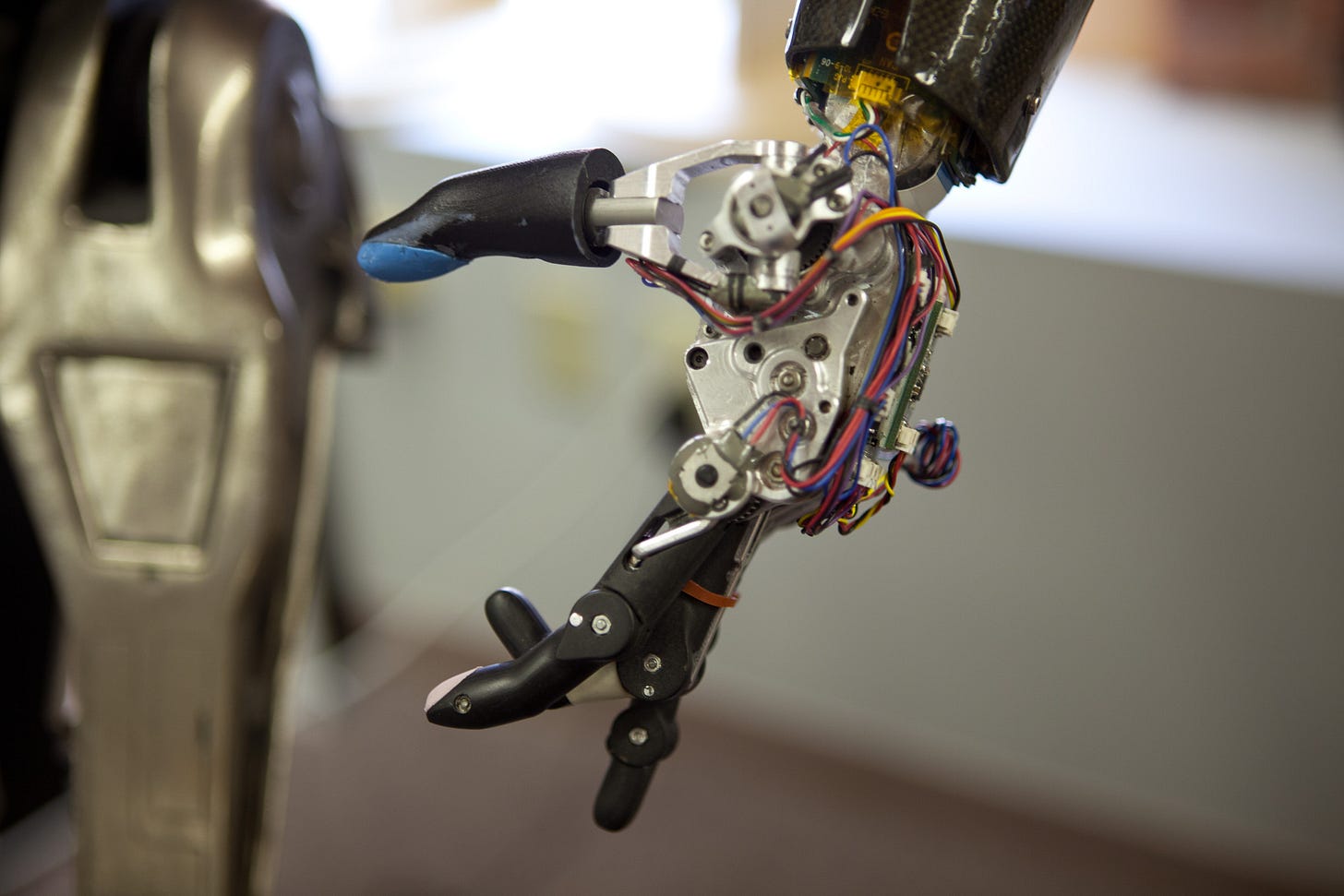

This is what greeted me when we entered:

Yes, that’s a T-800 Terminator. But you’ll notice that one of its arms has been removed and replaced by a smaller robot arm, a version of what they were developing at DEKA.

So, where was the terminator’s original arm? Nearby on a table next to another robotic arm and an unsettlingly life-like rubber hand skin-glove, as though the Terminator had just removed it to reveal his skeleton underneath.

You can imagine that this room was full of proprietary information. For every photo, I had to ask first, “Is it okay if I photograph this?” “What about this?” But I can describe a few things. There was an anatomical chart of a human hand on one wall. There was a poster of the Six Million Dollar Man on another wall. And quite a few model torsos with robotic prosthetics in various stages of development.

Dean found the latest Luke model. He asked if I wanted it with the rubber translucent skin or without, which is not something I had considered anyone would ever ask me. I said “with,” of course.

We headed back through the swipe-locked doors, up the stairwell, and through some more doors until we were back in the makeshift studio.

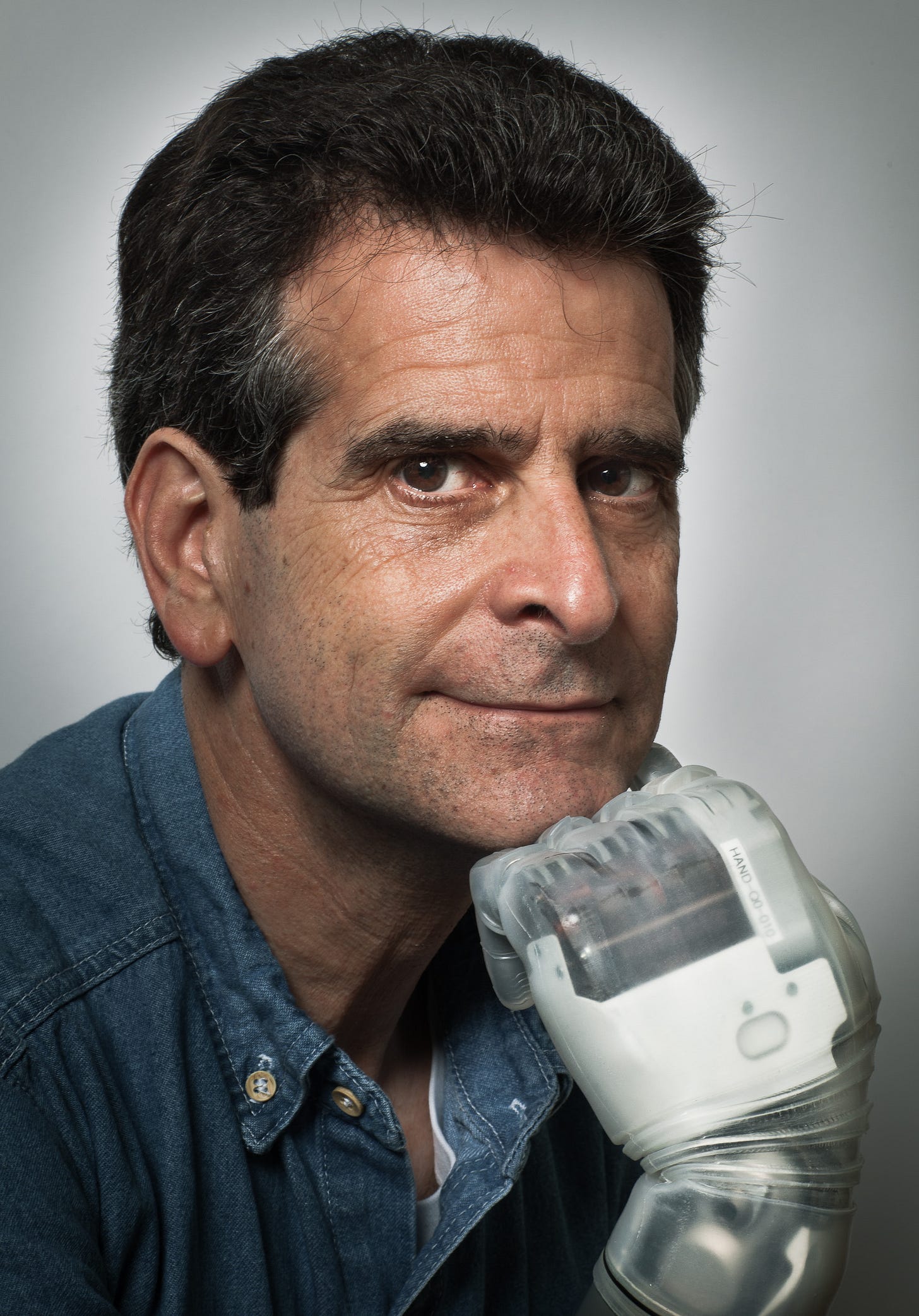

And that’s where I finally took this photo:

In the end, I don’t even think it was my favorite photo from the shoot. I think I like the one in front of the bookcase better. But I still like it. It’s pretty much what I envisioned.

More importantly, I learned a lesson that day which I still think of years later: When someone says you can’t do something, and you find yourself talking to the person who has the power to overrule them, always ask again. At worst, they say no. And maybe you get to see some cool robots.

And now, a thing to know:

You might know that RBG is an acclaimed documentary about the life of Ruth Bader Ginsburg (94% fresh). Although maybe you haven’t watched it yet. And you might know that Kanopy is an uncommonly good free streaming service that features a lot of classic films, indie films, and documentaries by major distributors, commercial-free, and all you need to access it is a library card or university login. Although maybe you haven’t signed up yet.

But did you know that RBG is available to watch on Kanopy?

Now you do. So if you haven’t seen it, or you haven’t signed up for Kanopy, there’s no better time to do both! 👩🏻⚖️

Thanks for reading. See you next week!

David