25 years ago, long before Virtual Reality was good enough and affordable enough for home consumers, there was another way to play 3D video games at home. It was surprisingly cheap, shockingly effective, and supported a huge library of games.

Allow me to over-explain.

Think for a moment about your computer screen. It has a refresh rate of probably between 60 and 120 times per second — it may be more or less, depending on the monitor, but let’s use 60 as a convenient number for our purposes. That means that it’s redrawing the image on your screen over and over again, 60 times per second.

If you’re doing something where the screen doesn’t change much, like reading email, not much needs to be updated with each refresh. But if you’re playing a game on your computer where your character is running around in a 3D world, the whole image on the screen has to be recalculated each time the screen refreshes. All the complicated math to figure out lighting, texture, perspective, etc, needs to happen 60 or more times each second. That’s why dedicated graphics cards are so important to gaming. They do the heavy math.

The graphics card is figuring out what the screen should look like from a single point of view. If it’s a first-person game, it might be the player’s point of view. Or it might be a virtual camera following the character. Either way, the computer is calculating what one “eye” would see if it were there.

So what if, every time it refreshed the screen, it shifted its point of view a couple inches to figure out what a second “eye” would see, and alternated between those two views with every screen refresh?

The result would be two distinct perspectives, simulating what a pair of eyes would see. But since they’re rapidly alternating 60 times per second, the result would look like two slightly different views superimposed over each other, similar to what you’d see watching a 3D movie in a theater if you took your glasses off. There needs to be a way to make sure that each eye only sees one of those views.

And that’s where a product called LCD shutter glasses came in. But first, let me talk about digital watches for just a second.

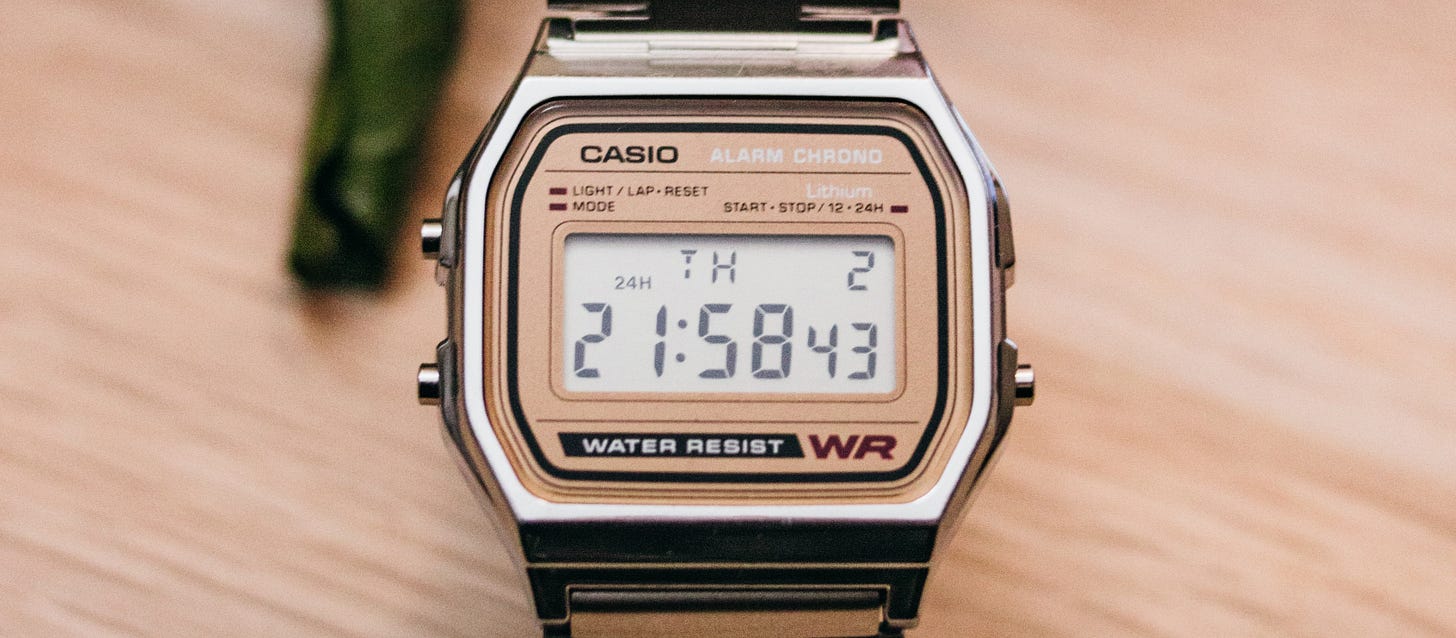

Remember old digital watches? The digits were simple liquid crystal displays, with each number made of seven liquid crystal segments. When one segment is charged with electricity, it becomes opaque. When the electricity turns off, it becomes clear.

LCD shutter glasses were just two big liquid crystal panels, one over each eye. When one panel is charged it becomes opaque, while the other is set to be clear. Then they alternate. This way, only one eye gets to see through a clear lens at a time.

If this happens fast enough, say, 60 times per second, it could be synchronized to the monitor’s refresh rate so that each eye only sees the image being rendered for that eye’s perspective. And at 60 frames per second or faster, you shouldn’t even notice that it’s flickering.

In order to achieve this synchronization, a thin wire connected the glasses to the computer’s video output, between the graphic card and the monitor.

The result: 3D gaming.

I bought one of these LCD shutter glasses, the ELSA Revelator, in 2000. It cost me a whopping $33.99 plus shipping. So cheap!

But that’s not even the best part. The best part is that games did not have to be specially designed for these to work. The glasses came with software that allowed almost any existing game to be played in 3D.

This meant popular titles like Tomb Raider, Thief 2, and pretty much anything else that used DirectX technology for rendering graphics would work.

Of course, unlike VR, there was no head-tracking back then. The display didn’t look like it was on a forty foot screen floating in front of me, or like the action was taking place all around me. I still had to sit in front of my computer and look at my monitor. But instead of displaying a flat game, the monitor became a window I looked through into another world where the game takes place.

With headphones on, playing Thief 2 in 3D — a game where your character accomplishes goals through stealth rather than combat — my heart raced as my character snuck up behind a guard to steal his keys, or hid in the shadows, or crossed a wooden rafter with a long drop to the ground below. Being able to actually see how far the drop is in 3D brought the game to a whole new level. It was the most immersive gaming experience I ever had up to that point.

Tomb Raider wasn’t a first-person game. But in 3D, Lara Croft became a Barbie-sized figure running around a tiny landscape, firing at enemies, all happening inside my monitor like a moving diorama.

The full truth is that the glasses weren’t a perfect experience. At 60 frames per second, you can actually see some flicker (although a higher-end monitor with a faster refresh rate would have been better than my cheap Dell model). And the shutters cut the light reaching your eyes in half, so it was like playing a video game with sunglasses on. You had to turn up the brightness on your monitor to compensate. And very occasionally, the glasses would get out of sync, resulting in a flash of light getting through both eyes at the same time, which was a bit annoying. But it was worth the trouble for such an incredible experience.

The barrier for entry for these glasses was so low, I didn’t understand why everyone didn’t play games this way.

The VR Equivalent

Fast forward to today. VR is affordable, and in many people’s homes. It hasn’t reached critical mass yet, but with more major companies developing AR and VR devices, interest is growing.

There are a lot of games already available for VR headsets. I’ve played many of them and there are some true quality gems to be found. But there’s also a group of people who are hacking old games that weren’t designed for VR and getting them to play in Virtual Reality.

The first such game I played in VR on the Meta Quest was Doom 3, an atmospheric and terrifying game that first came out in 2004. No VR version has been officially released. But a group of clever folks who call themselves Team Beef figured out how to get it to work.

To be clear, this does not involve any piracy. You still have to buy the original game, which costs just a few dollars these days. Then by following their simple instructions, you can sideload it onto the Quest along with Team Beef’s loader that converts it to a Virtual Reality game.

It was unsettlingly scary. Monsters hid in the shadows and terrified me. The game translated extremely well to VR and was better than a lot of made-for-VR games I’ve played.

But Team Beef kept going. They’ve got other classic games working in VR like Jedi Knight II, Quake III, Duke Nukem 3D, and Return to Castle Wolfenstein.

They’re putting a lot of work into each of their ports. But what if it were as easy to convert a game to VR as it was to play games in 3D with the shutter glasses? Games still use DirectX and similar technologies. Could someone make software that just turns every DirectX game into a VR game by rendering two perspectives and outputting it to a headset?

Well, sort of. There is at least one product that claims to do exactly that. It’s called VorpX, which is a name that I’m sure makes sense to someone. And there’s an open source project called Vireio (ugh, these names) that attempts to do the same thing.

I have not used these products myself — they only run on Windows, which I’ve long since moved away from — but from what I understand, I’m not missing much. It turns out that it’s not so easy to make a one-size-fits-all solution. Most games weren’t developed for VR controllers, or with graphic assets for virtual hands that interact with the 3D world. So even though a player may see the scene in 3D in your headset, you often have to use a traditional video game controller or a mouse and keyboard to play. And the disconnect between what your body is doing (sitting still) and what your eyes see (moving around) causes dizziness in a lot of people.

But I like the potential.

The Future of 3D Gaming

Putting on a headset to play games isn’t for everyone, but I remain bullish on 3D games. I’ve been playing in 3D for 23 years (longer if you include the time I played Dactyl Nightmare at the mall in 1991) and seen waves of experimentation and popularity. There were LCD shutter glasses made for home consoles when manufacturers were pushing 3D TVs, but they didn’t take off. And things like Google Cardboard were just clunky and unpleasant to use. Nintendo tried a couple different approaches with the Virtual Boy and 3DS consoles, to mixed results.

Now that Apple has entered the VR/AR market with their Apple Vision Pro, people are taking headset computers seriously again, after laughing off Meta’s ill-defined metaverse. Even though Apple didn’t position their product as being for games, I have no doubt that will come. And as the products get better and prices get lower, I think people will be more open to 3D gaming.

I guess what I’m mainly trying to say is that I really want to play Thief 2 in VR. Can someone work on that please?

Thank you for reading another newsletter! I have a couple irons in the fire for upcoming issues that I’m pretty excited about and can’t wait to share with you in the weeks to come.

Until then, keep your feet on the ground and keep reaching for the stars. (I never know how to sign off on these things.)

David

I actually wrote my first whitepaper on the history of stereoscopic video games for the Stereoscopic Displays & Applications conf.

https://library.imaging.org/admin/apis/public/api/ist/website/downloadArticle/ei/30/4/art00014

For all you NERDDDS ;)