The 32nd person in my inventor profile series was Steven Sasson, the inventor of the first digital camera. He invented it at Kodak in 1975, but they weren’t interested in creating a new product category that would compete with their film business, so it basically sat on a shelf for decades.

By this point in my project, I had learned that to arrange a shoot with someone like Steven, the proper way would be to go through Kodak’s PR department. But I also knew that it would be a lot easier if I had someone on the inside to help grease the wheels. After a bit of sleuthing, I found Steven’s email address and just reached out to him directly. He was more than happy to help arrange a shoot.

[Tip: if you ever need to find someone’s email address at a big company, the website email-format.com is a great tool for figuring out their likely address. I have used it successfully to cold-email people plenty of times.]

So off I went to Rochester, New York, home of Kodak headquarters.

When in Rochester

As long as I was in the vicinity, I went to Kodak founder George Eastman’s house, which has been turned into a museum.

They had a life-size replica of Mr. Eastman sitting on a couch reading.

There was one part of the museum where photography was not allowed. I found that ironic. So I took a photo of the sign telling me photography was not allowed in the home of the man who brought photography to the masses.

And I stayed at a hotel that apparently had a lot of rooms:

The Pixel Chair

When I arrived at Kodak’s headquarters, I ran into a familiar situation. The PR department wanted me to shoot Steven in the room where they do all their interviews and photo shoots. This meant my images would look similar to pictures other people have taken, and I didn’t see much point in that. So I've learned to always ask to see another option.

They took me to an executive meeting room that had some tables and shelving units with displays of Kodak’s latest cameras. But what caught my eye was this chair:

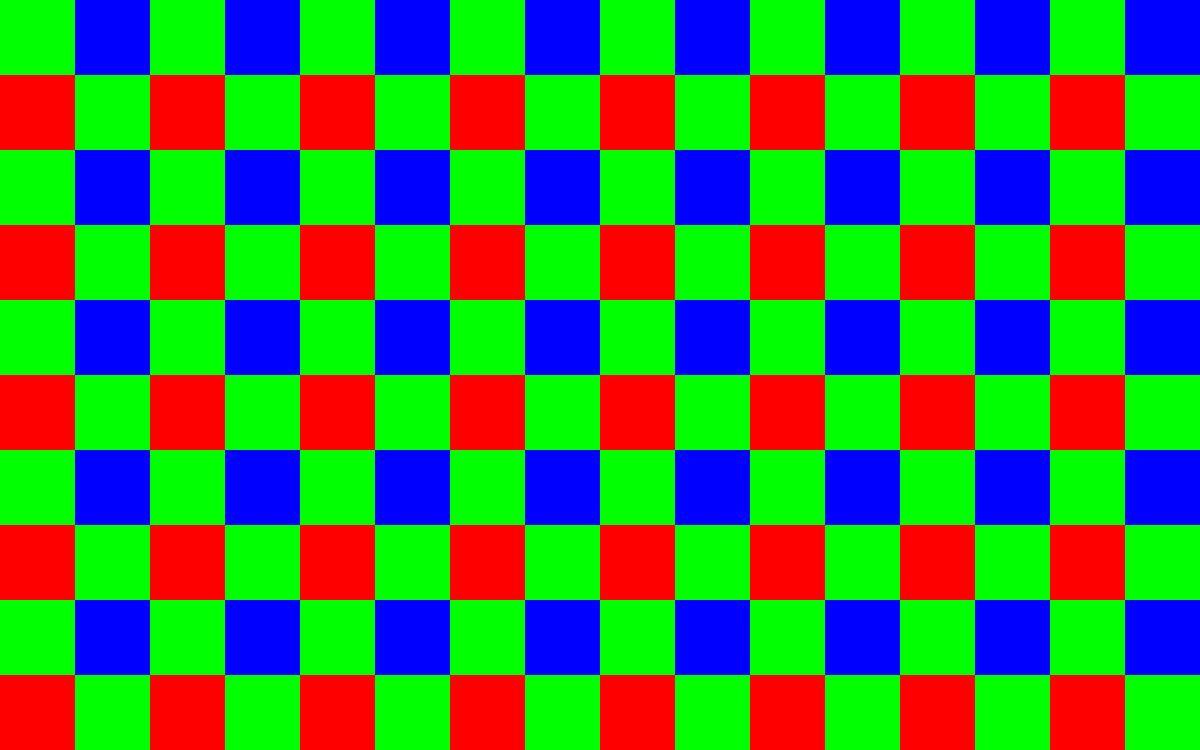

Each pixel in a digital photo contains some combination of red, green, and blue that together create the pixel color. But the pixels in a digital camera sensor are each actually only sensitive to one of those colors. The information captured by each of those pixels is averaged together with the pixels around it to figure out what color each pixel should really be. The pattern of color-sensitive pixels looks like this:

So when I saw that chair, I was immediately reminded of this pattern and it became the perfect place to photograph the inventor of the digital camera. It was a very subtle connection that I didn’t figure most people would pick up on consciously, but that made me like it even more.

The Camera

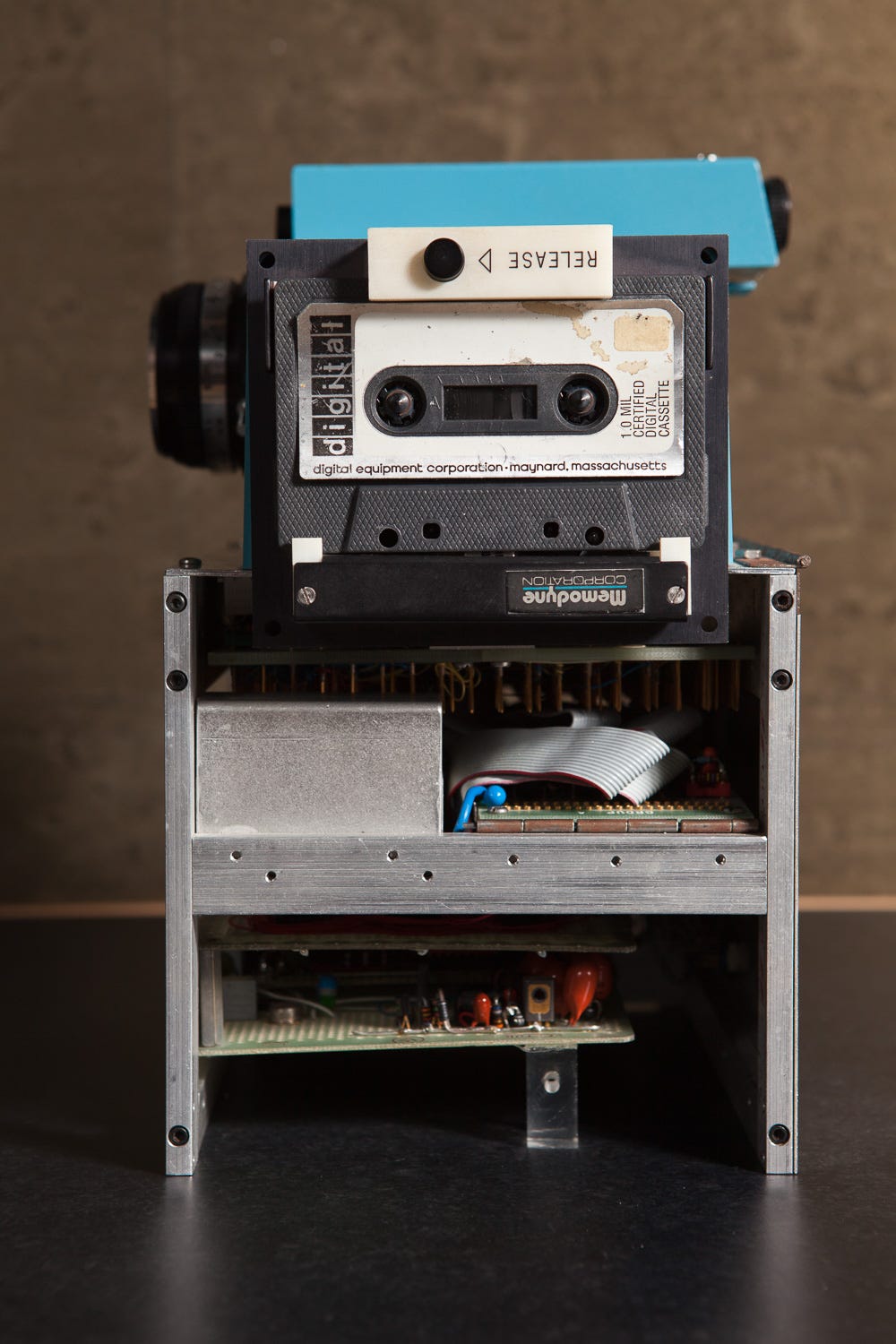

Want to see what the first digital camera looked like?

The sensor was a 100 x 100 pixel CCD. The lens assembly came from a used parts bin from a manufacturing floor. The rest of the parts came from various places around the lab.

There was no removable memory card for storing photos. Instead, images were recorded onto a digital cassette. Steven designed the system so a cassette would hold 30 images, a number he chose to be in between 24 and 36, which are the standard numbers of frames you could take with a roll of film (is that something people generally know these days?). He could have made it store more. So why did he limit it to 30?

I knew that I would be compared to film, obviously. I could’ve stored hundreds of images on this tape but I didn’t want to confuse the issue. I didn’t want to say, “Oh I can store all these images on here” and then all of a sudden people are worried about storing all the images on one thing and that wasn’t the point. I wanted it to be like a camera. So I adjusted it so that it would be a number that people were more familiar with.

His rationale sounds very much like the MAYA principle, a strategy developed by mid-century industrial designer Raymond Loewy. MAYA stands for Most Advanced Yet Acceptable. It teaches that products should be designed with just the right balance of innovation and familiarity, or people will reject it.

That principle is basically what Steven tapped into.

The key, I think, when you’re putting across an idea is you have to understand the culture you’re dealing with, first and foremost, and put everything very much like the culture is used to. And then put only the essential elements of your idea out there so that it doesn’t get confused with things that might complicate the concept.

So that was kind of a long-winded description of why I chose 30.

Unfortunately, the digital camera may have still been a little too advanced for the folks at Kodak, and by hiding it away, they missed their opportunity to lead the digital space.

Here’s a video I made with Steve talking about the camera, showing off the inner workings, and demonstrating how you would use it to take a picture:

And here’s some trivia for you. The first digital photo ever taken was of a lab technician named Joy Marshall:

I decided to pack the camera up and carry it down the hall outside our lab and found a lab technician sitting at a teletype machine. I asked her if I could take a head and shoulders shot of her and she agreed. Snapping the picture, I went back to the lab to remove the tape, place it in the playback unit to see the result. When the picture appeared on the screen you could see the outline of her hair and the light background, but her face was complete static, totally unrecognizable.

Jim [Schueckler] and I were overjoyed at what we saw because we knew a thousand reasons why we might not see anything at all. I remember saying to Jim, “So much is working.” Joy, who had followed us back into the lab was less impressed with the resulting image and said, “Needs work” and then left the lab.

It turned out that when I designed the playback system I [long technical explanation deleted]. We figured it out after about an hour and corrected it. Then the picture appeared correctly. That was the first image taken of a subject and it took place in early December, 1975.

Unfortunately, I didn't save the image.

That’s it for another edition of the newsletter. While you’re poking around the internet, you should check out Buffalo-based photographer Luke Copping. Twelve years ago, he assisted me on this shoot at Kodak and a few others I had in the region. I’ve followed his work since then, and he’s become quite a good photographer! I particularly enjoy his new Messy Food series that he’s been posting to Instagram.

See you next time!

David

Sadly, I did not get your hotel joke until the second reading.