The Last Calendar You’ll Ever Need

The best calendar is the one you have already. Or at least it should be.

I haven’t really used a wall calendar in probably 20 years. Like most people, I use a digital calendar to track important dates and meetings. But a few years ago, when I still used to go into an office and work in a cubicle, I purchased a calendar to adorn my cubicle wall. It was the 2019 Sears calendar by pop artist Brandon Bird.

Each month featured a different painting of a Sears store. Some paintings were realistic, and others were almost abstract in their composition. It was the perfect amount of kitsch for an otherwise fairly unadorned cubicle.

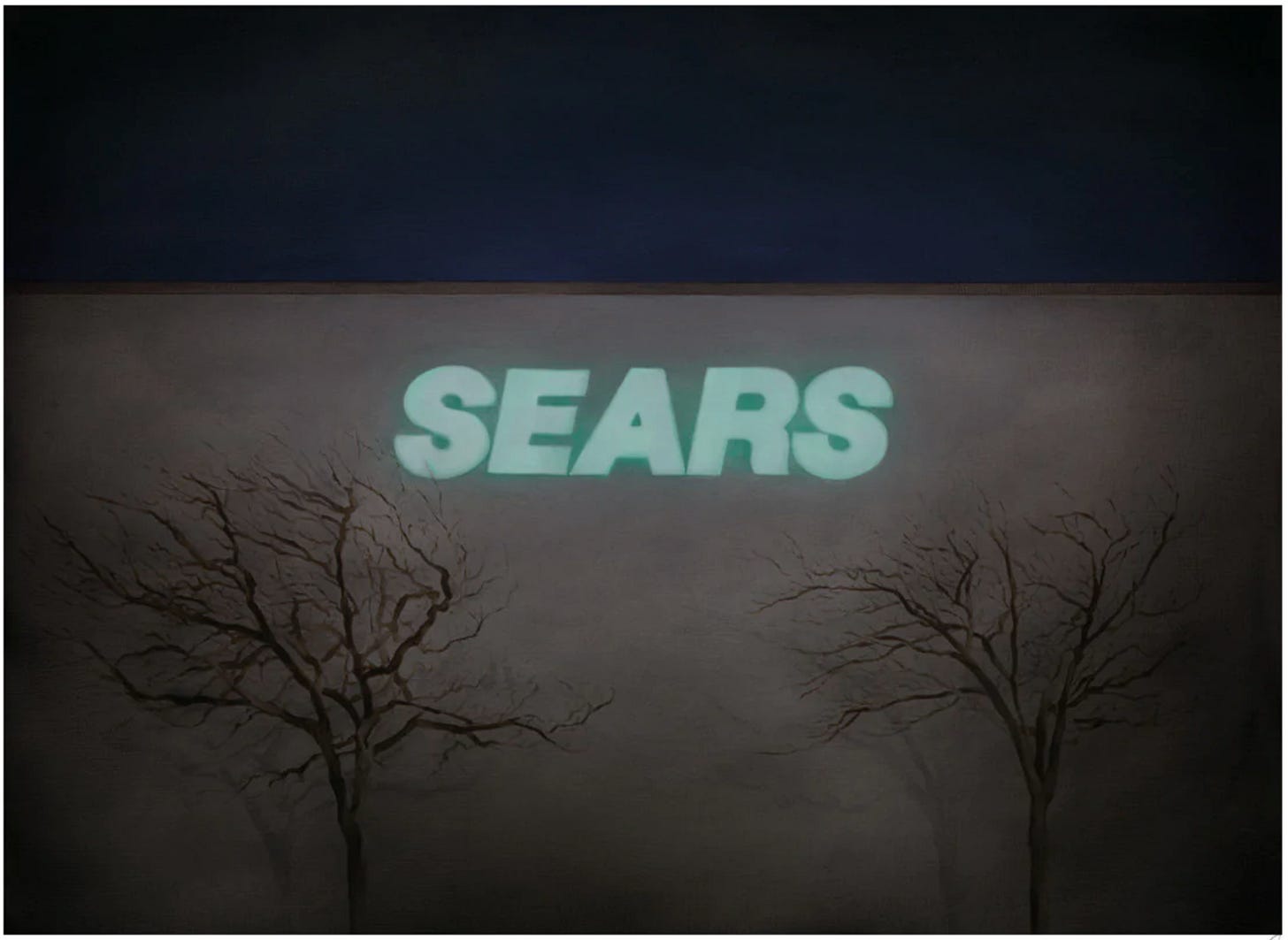

My favorite painting in the calendar was “Night Sears,” depicting a store in Flagstaff, my old stomping ground. It was the image for October, which we can all agree is the best month of the year.

Then there was “Sears: Bakerfield” with such a rich texture on the stonework that you feel like you can reach out and touch it:

It was a great calendar. It felt like something that might be given to employees at a Sears corporate retreat if executives had any taste.

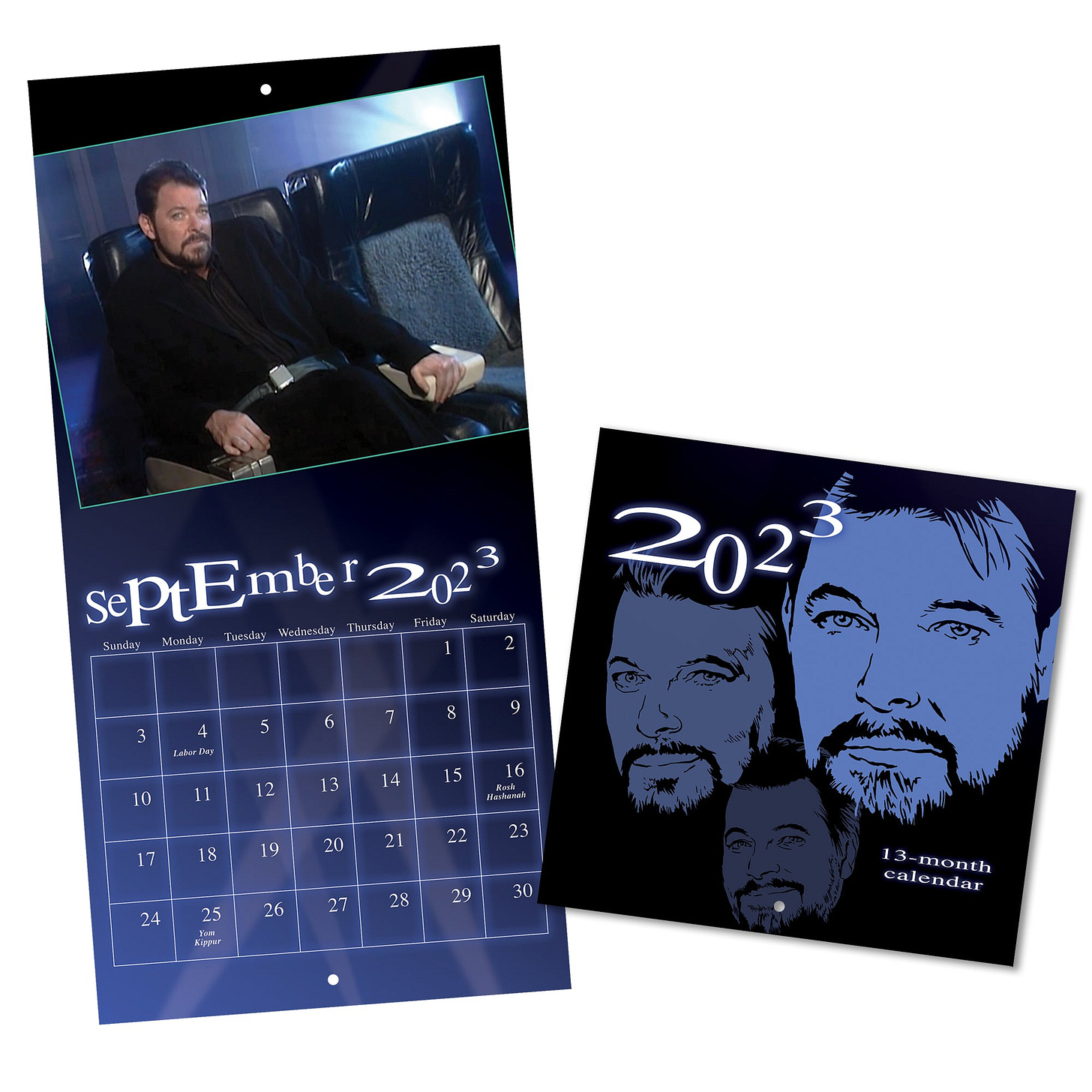

I was sad when 2019 ended and I couldn’t use it anymore. The next year, Brandon didn’t make a new Sears calendar. Instead he came out with a Jonathan Frakes calendar, which wasn’t really my style.

There’s a website called WhenCanIReuseThisCalendar.com that will tell you when your old calendar can be reused. It turns out that if I hold on to the 2019 Sears calendar, I can reuse it in 2030, and then again in 2041 and 2047. I’m probably not going to do that.

But all of this brings me to the real topic of this week’s newsletter: Why don’t we just have a system that lets us use the same calendar every year?

The Invariable Calendar

In the summer of 1910, an international group gathered in London to consider that very question. Delegates from governments around the world convened to form the International Chambers of Commerce, and this topic was on the agenda.

The idea of calendar reform wasn’t entirely new. There were many different calendars in use around the world, varying by region and culture, and it was obvious for a while that a standard would be helpful. By the time this group convened, most of the world had adopted the Gregorian calendar that we use today, but several major nations had not, including China, Russia, Greece, and Turkey.

At this gathering, there were a number of proposals put forth for how to handle the 52 weeks of the year. Some suggested dividing the year into 13 months of four weeks each. This was dismissed because businesses would lose the ability to divide the year evenly into quarters. Other people suggested 52 weeks with no reference to months at all. But one proposal in particular was favored above the others. It was developed by a Swiss Professor named Grosclaude who had gained traction with his idea since debuting it ten years earlier. The New York times described his idea this way:

Prof. Grosclaude proposed that the quarters should be composed of ninety-one days each, as this number is divisible by seven, each quarter being thus composed of thirteen weeks exactly. The two first months of each quarter would have each thirty days and the third one thirty-one. This gives us in all for the year 364 days.

In other words, we would still have 12 months. The number of days in each month would go like this: “30 days, 30 days, 31 days” then repeat. There are a number of advantages to this plan, including:

This gives us four even quarters.

Every quarter starts on a Monday and ends on a Sunday, which makes accounting consistent for businesses.

Every year, the same date falls on the same day of the week, which makes planning easier.

Any calendar is infinitely reusable.

But, I hear you saying, there are not 364 days in a year. There are 365, and sometimes 366 on a leap year. So what happens then?

Prof. Grosclaude proposed to intercalate between Dec. 31 and Jan. 1 a day to be called New Year’s Day, and for leap years he would place another day between June 31 and July 1, which he would call “Leap Day.”

So New Year’s Day and Leap Day would be distinct from days of the week. That is, you wouldn’t say New Year’s Day falls on a Monday, but rather that it comes between Sunday and Monday. It’s a little weird because it’s not what we’re used to, but I also kind of love it.

Maybe you’re more of a visual person. Here is a diagram illustrating how Grosclaude’s calendar would work:

Look at the beautiful simplicity. We keep the months and their names as we know them. We just change them to have 30, 30, and 31 days, and then repeat that pattern. We still get to have quarters, and we get an extra day off for New Year’s and Leap Day. It’s so elegant.

So what happened?

The International Chambers of Commerce liked the idea. They spent quite a bit of discussion concerned with making sure that Easter would fall on a consistent day each year, but with everyone in eventual agreement on that matter, they made the recommendation to the Swiss government that the invariable calendar should be adopted and that they should “provoke an international political conference” to discuss the matter.

The recommendation was backed by other groups including the International Astronomical Union, which you may remember is the group that later redefined planets to exclude Pluto. They’re not afraid to shake things up!

Things moved slowly, but finally the Swiss government forwarded the topic to the League of Nations, a predecessor of the United Nations formed after World War I, which put it on its agenda for discussion.

According to a 1947 issue of The Journal of Calendar Reform (which was apparently a thing), the idea hit a wall around 1924 when the League of Nations decided to consult religious authorities. They met with the Vatican, the Ecumenical Patriarch, and the Archbishop of Canterbury. They were all fine with the plan for calendar reform, but only if it was “definitely demanded by public opinion” for the “improvement of public life and economic relations.”

And so the League sought public consensus. And if you’ve ever tried to get consensus on anything, then you can imagine that once they started asking for public opinion, even more ideas for calendar reform came pouring in. More organizations were formed to promote different versions of the calendar. More international meetings took place to examine the benefits of one idea over another.

A calendar called The World Calendar, similar in many ways to Grosclaude’s calendar, gained some traction in the 1930s when it was proposed by a new group called the World Calendar Association. We’ll come back to them in a minute.

After World War II, the United Nations became the new forum for consideration of the invariable calendar. But when the subject was raised in 1955, the United States opposed calendar reform, writing to the U.N. Secretary-General:

This Government cannot in any way promote a change of this nature, which would intimately affect every inhabitant of this country, unless such a reform were favored by a substantial majority of the citizens of the United States... Large numbers of United States citizens oppose the plan for calendar reform that is now before the Economic and Social Council. Their opposition is based on religious grounds, since the introduction of a "blank day" at the end of each year would disrupt the seven-day sabbatical cycle…

This Government, furthermore, recommends that no further study of the subject should be undertaken.

Come on! Religious grounds? Even the Vatican was okay with it! And so we are stuck with the Gregorian calendar, and no consistency from year to year.

But amazingly, the World Calendar Association did not give up. It continued to remain active in advocating calendar reform all the way up until at least 2013. Their last Director died in 2020.

This was their most recent flier promoting The World Calendar, which you can see shares a lot in common with Grosclaude’s invariable calendar. But this variation puts the 31-day month at the beginning of each quarter rather than the end, and has quarters beginning on Sundays rather than Mondays.

In order to make a seamless transition, the Association recommended The World Calendar be adopted in a year where January 1 already falls on a Sunday. It turns out that 2023 is such a year. If we are going to move to the World Calendar, our next opportunity won’t be until 2034. I guess maybe I will hold on to my Sears calendar until 2030 after all.

Meanwhile, if you have a calendar from 2017, 2006, 1995, 1989, or 1978, you can use it again now for 2023.

And Brandon has a new Jonathan Frakes calendar available, if that’s your thing.

And that’s it for another newsletter! A huge welcome to the ton of new subscribers who signed up after the last issue, which was by far my most-read issue yet. And a big thank you to everyone who shared the last newsletter, which is the best way to help it grow. Maybe you’d like to share this one, too?

Until next time, thanks for reading!

David