If you haven’t checked out the Ironic Sans YouTube channel yet, now’s your chance!

Of all the interviews I did for my Inventor Portraits Project, there is one quote that I come back to perhaps more often than any other:

There's two types of inventions. There are inventions that are what we would call a natural evolution, that if that person didn't come up with it somebody eventually would've. Like, for example, the windshield wiper. If somebody didn't invent the windshield wiper, eventually somebody would've come up with it. But then there are those more personal things that if the inventor didn't come up with, it would've never existed in the world. And that's more like art. And that's what I try to do.

It seems a bit obvious once said out loud, but that distinction between two types of inventions has ended up relevant to a surprising number of conversations over the years. The person who said it was Mark Setteducati, the 41st inventor in my project, and one of the most creative and clever people I profiled.

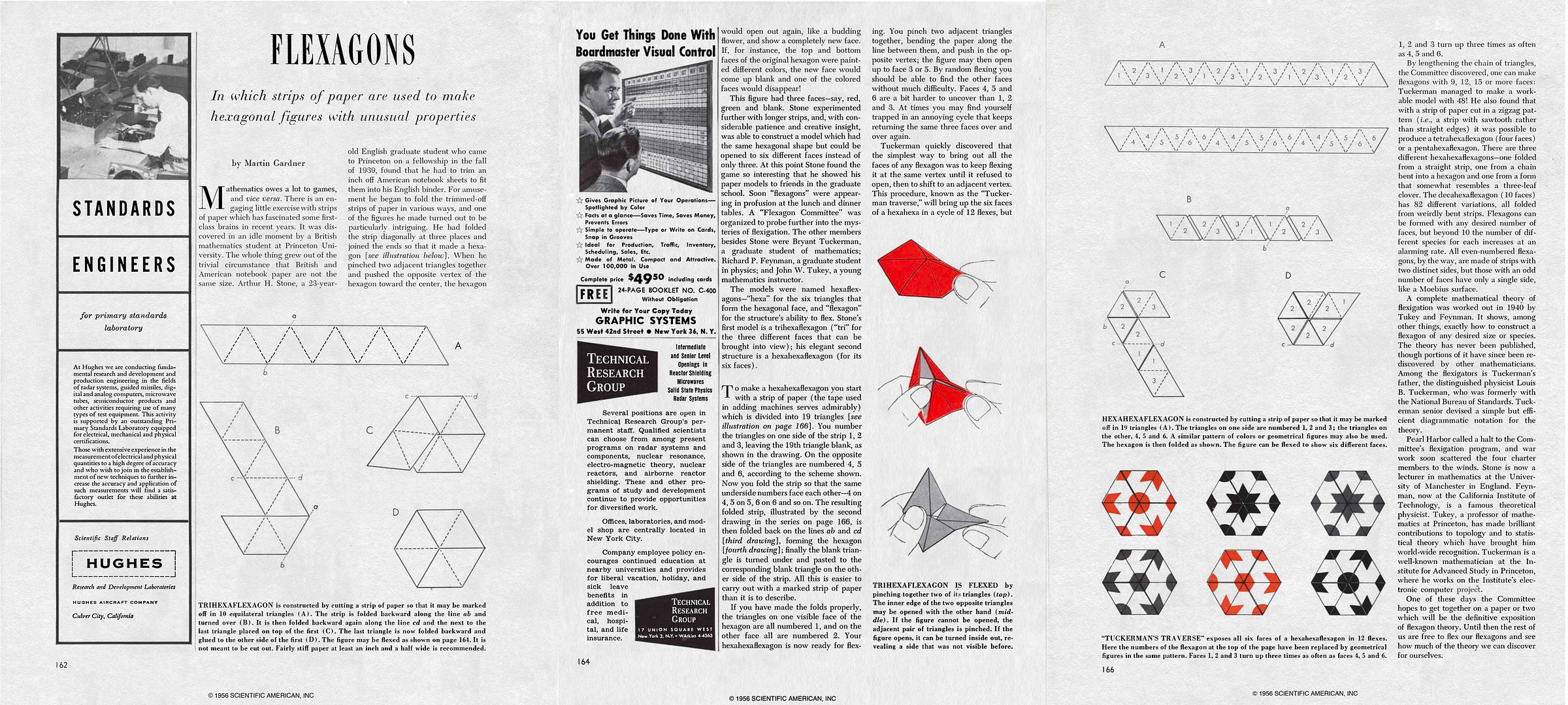

Mark is an inventor who uses principles of science, math, and magic to develop toys and games. He’s a graduate of New York’s School of Visual Arts, and former assistant to artist Louise Bourgeois. But his life of invention began when he saw an ad for a company inviting people to develop new ideas for hexaflexagons.

A hexaflexagon is a mathematical object that’s fun to play with and easy to make at home out of a strip of paper. This classic video by Vi Hart is a wonderful introduction to them:

The big revelation that Mark had while developing ideas around hexaflexagons was that the company interested in developing the product was offering to pay him a royalty. He liked the idea of receiving a continuous money stream just for coming up with an idea, and that became the business model for his career:

I pursue coming up with ideas and pitching them to toy companies, kind of like an author with a book. You come up with an idea and you make a prototype or a presentation, you show it to the company and if they buy it, you make money, royalties. And if they don't, back to the drawing board or try somebody else.

Mark is a skilled magician — a lifetime member of Hollywood’s Magic Castle — and his particular interest is figuring out how to use principles of magic in toys and games.

For example, Mark frequently employs mirrors that create illusions in his toys, like this Mona Lisa puzzle where you complete half of it on “this” side of a mirror, and half of it simultaneously in its reflection:

Or this game, where what appears to be one large cube is actually four small cubes sitting on a mirror, and they can be rearranged in different ways to solve various puzzles:

In 1999, Mark co-authored a very clever book called The Magic Show. It’s a unique type of pop-up book that actually performs a magic show! It’s fun to go through once and experience it, and then examine it more closely to figure out how all the tricks work. Someone has filmed a complete walk-through of the book that you can see here. A classic card trick begins at around 3:20. See if you can figure out how it’s done:

So how does a creative guy like Mark come up with his ideas? Some people start with a goal — I want to make a game about the stock market, or I want to make a magic trick where a pencil levitates — and then figure out how to do it. But Mark works the other way around:

The way that I prefer to invent is I find intriguing principles such as a mathematical principle or an illusion or reflective principle. So I start with the principle. I find different principles by just observing nature.

So many times in real life we're actually fooled by, we accidentally walk into a glass door and we didn't realize it was there, or we think there is something there and it turns out to be a reflection.

So when I notice things like that, I say, "Wow, there's a trick there." I automatically think, "Oh, that's something." I love being fooled that way spontaneously because then there's the basis of something that I can explore and maybe make even more amazing and make it intentional instead of accidental.

Many years ago, Mark co-founded a bi-annual gathering of math and puzzle fans called the Gathering 4 Gardner, named for the mathematician Martin Gardner who had a column for many years in Scientific American where he popularized, among other things, hexaflexagons:

One of the great things about an event like the Gathering 4 Gardner is that it brings together people from related but not identical fields where chance encounters can lead to new innovations:

At the Gathering 4 Gardner we have many different types of people. We have magicians, we have people that do origami, we have people that do puzzles, we have mathematicians. It's a diverse group of people that come together.

I also go to magic conventions, but then you have just magicians. And I also go to puzzle conferences or a toy show, then you're just with people that do toys or puzzles.

But the Gathering 4 Gardner is unique because people that have some kind of common thread, because we're all interested in these beautiful principles, whether mathematical principles or magic or puzzles, but we come from diverse areas, people from universities, people that are magicians or puzzle collectors or designers, and we speak about our interests.

And we come into contact with many people that we would have never come into contact in our own field.

It was at a Gathering 4 Gardner that Mark met Ken Knowlton, a computer scientist who worked at Bell Labs in the 60s where he created digital mosaics.

Sidebar: In 1967, the New York Times published Ken Knowlton’s mosaic titled “Computer Nude (Studies in Perception I)” — the first time the Times ever published full frontal nudity!

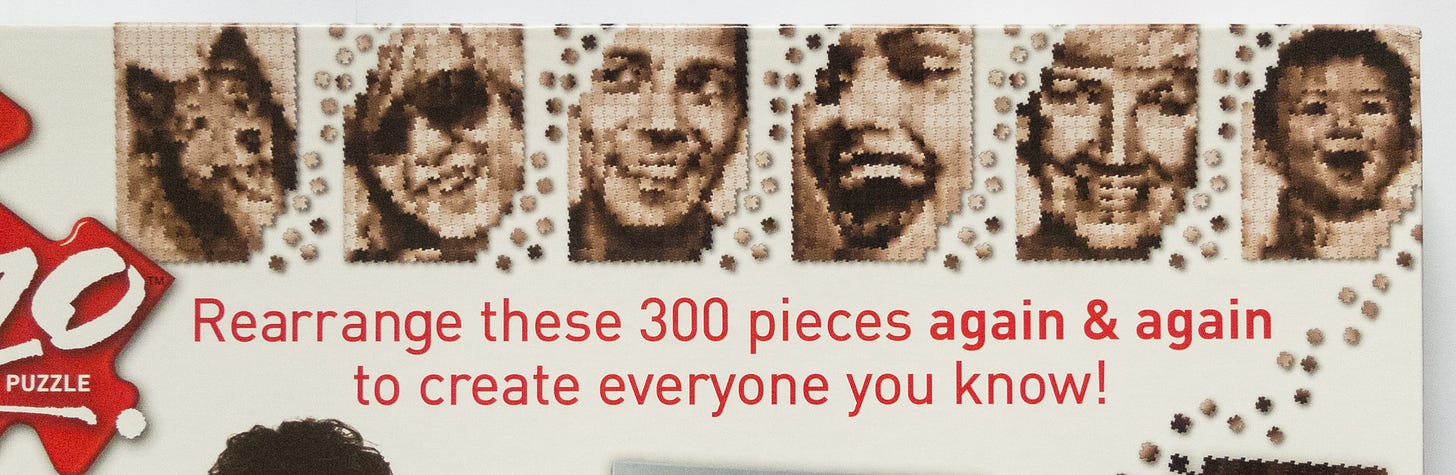

Ken and Mark eventually collaborated on an innovative product called Ji-Ga-Zo, a 300-piece puzzle that can be rearranged to create a low-resolution mosaic of anyone!

The product was released first in Japan by a company that named it Ji-Ga-Zo because that's the Japanese word for Self Portrait. It was a happy coincidence that the name kind of sounds like the word “jigsaw” so they kept the name for the English version, too. Here’s Mark with the Ji-Ga-Zo puzzle of himself:

Perhaps unusually for an inventor, Mark doesn’t care about patents even though he has several. But he makes a good point abut them that applies to pretty much any creative field:

I don't really care too much about patents. And that might sound funny from somebody that has so many patents. But the patent process itself is very seductive because it feels like you're doing something very important, filling out all that government forms, and then they send you a nice document, and it feels like you actually did something really important.

You invented something

But that's really pretty meaningless. The only thing that's meaningful is getting it out into the market, getting your ideas out there in some way. So the patent part, to me, is just a very small technicality.

I have certainly fallen into that trap before, getting caught up in parts of a project that feel important but ultimately get it no closer to being out there for people to experience and enjoy.

And speaking of things to experience and enjoy, here is the video I made about Mark and his inventions. Please experience and enjoy it!

And that brings another newsletter to a magical close! If you have a piece of paper lying around and a few minutes to spare, you should really make yourself a hexaflexagon. Here’s Vi Hart again with her definitive guide to making one:

If it helps, you can download a PDF of her template here. Have fun, and I’ll see you next time!

David